Nikhil loves his country as much as, if not more than, Sandip, but he will not allow his love for the country to overtake his conscience.

In the absence of truly benevolent leaders like Nikhil, she would be mutilated, divided in two (currently Bangladesh and West Bengal), with millions of her children paying with their lives to meet the apocalyptic wishes of self-seeking, immoral, power-hungry politicians, determined to carve out her body on religious communal lines.

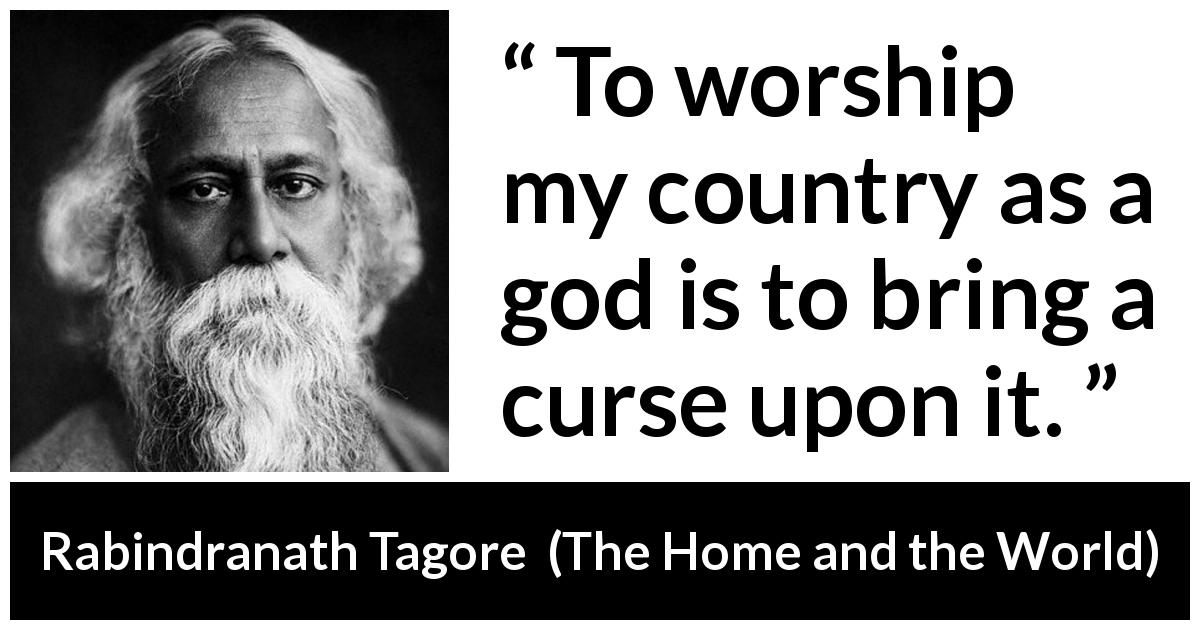

Seen from this perspective, Nikhil’s death at the end of the novel, just when Bimala is turning the corner and returning to her senses after a prolonged infatuation with Sandip and his views, also signals Tagore’s pessimism about the future of Bengal. On the other hand, Sandip’s parochial and belligerent nationalism, which cultivates an intense sense of patriotism in individuals, threatens to replace their moral sensibility with national bigotry and blind fanaticism. Nikhil’s vision is one of enlightened humanitarian and global perspective, based on a true equality and harmony of individuals and nations. The novel has a certain allegorical quality in that Nikhil and Sandip seem to represent two opposing visions for the nation with Bimala, torn between the two, not knowing for sure what should be her guiding principle - signifying Bengal tottering between the two possibilities. At the sight of Sandip, she emotionally trips, vacillates between him and her husband, until she returns home bruised and humiliated but with a more mature understanding of both the home/self and the world. The novel deals with the experiences of three characters during the volatile period of swadeshi: Nikhil, a benevolent, enlightened and progressive landlord his childhood friend and a voluble, selfish but charismatic nationalist leader, Sandip and Nikhil’s wife, Bimala, who is happy at the outset in her traditional role as a zamindar’s wife but who, encouraged by her husband, steps out of home to better acquaint herself with the world and find a new identity for the Indian woman. The controversial nature of the subject matter, in which Tagore takes the opportunity to launch his fiercest attack yet against the ideology of nationalism, contrary to its rising popularity both in India and the West, was also a reason it drew much attention, mostly in the form of reprobation and scorn, from readers both in and outside Bengal. The novel deals with the experience of modernity and the price one has to pay for it. Rabindranath Tagore’s Home and the World is a product of the crisis of that time, and as a political novel it echoes through its narration a large number of attitudes, not always compatible with the colonial experience.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)